Is it plausible that the Christian depiction of the cross originated from earlier sources, or are there alternative theories? Additionally, which ancient civilization first developed this form of execution?

Here’s a concise look at both questions:

- The “shape” of the Christian cross

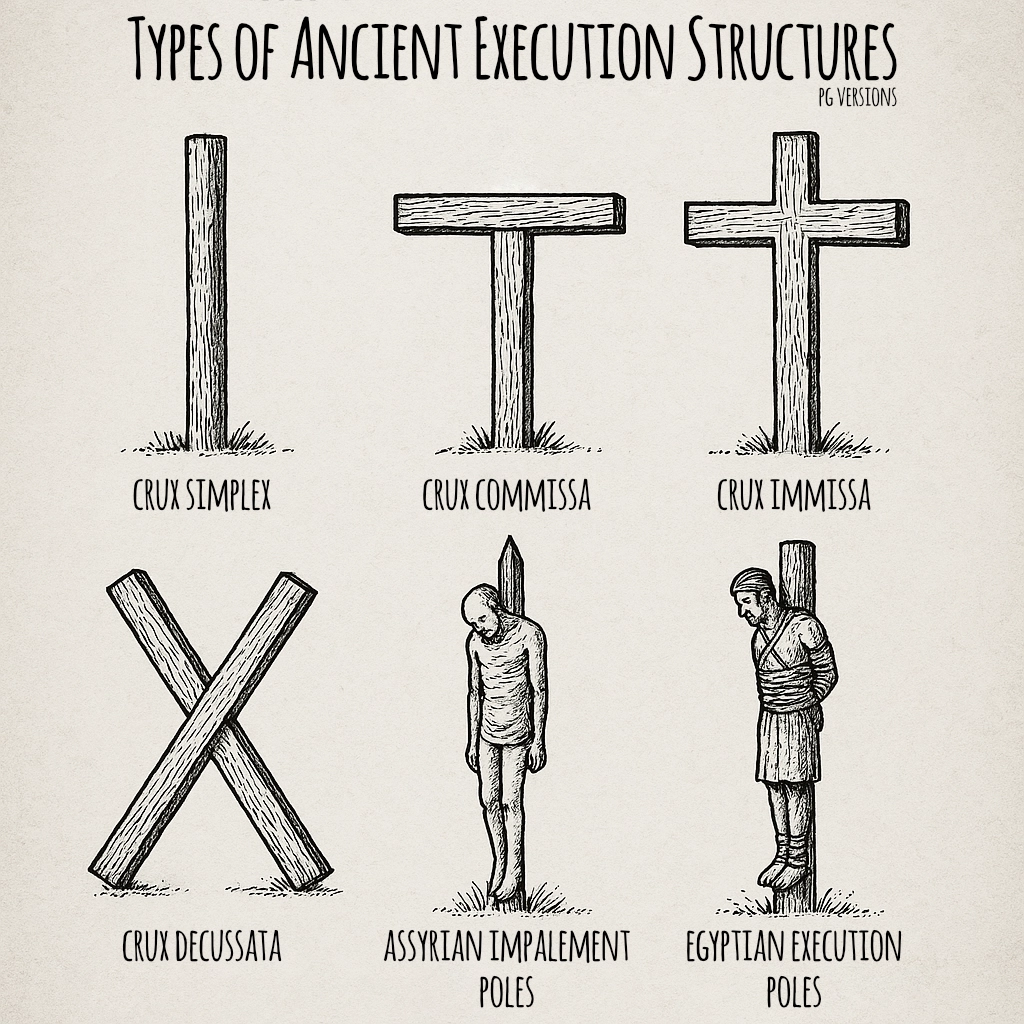

- Early Christian writers never give a precise blueprint of Jesus’ gibbet. Justin Martyr (circa 150 AD) simply refers to “two pieces of wood” joined to form a cross, without clarifying whether it was a †, a T, or even an X [1].

- Roman executions, however, employed a variety of shapes. Seneca the Younger notes “crosses… made in many different ways: some with the head down, some impaled, others with arms outstretched”[2].

- Scholars generally conclude that the standard crux immissa (†-shape: a vertical stake plus a transverse beam) became dominant in Roman Judea by the 1st century AD—hence its adoption by Christians as the symbol of Christ’s death. But a crux commissa (T-shape) or even a single stake (crux simplex) remains viable historical options.

- Who “invented” crucifixion?

- Impaling or “hanging on wood” appears in Egypt as early as the New Kingdom (circa 16th–12th century BCE). Merneptah (reigned 1213–1203 BCE) boasts of setting enemies “on stakes” outside Memphis [3].

- In Mesopotamia the Assyrians depicted captives strung on poles (e.g., Lachish reliefs, 701 BCE). Persia’s Darius I crucified some 3,000 foes in Babylon (circa 520 BCE).

- Phoenicians/Carthaginians, Greeks and later Romans all adopted variants. Rome perfected crucifixion into a formal capital-punishment—designing crossbeams you carried to your own execution, fixed uprights in the ground, nailing or binding through wrists and ankles, even offering a footrest mid-post to prolong agony.

— So, while the †-shape is the most plausible model for Jesus’ cross (and thus the Christian emblem), ancient crucifixion actually evolved over many centuries across Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, Carthage and Rome [4].

Have there been any archaeological discoveries that support these various interpretations?

Here’s the state of archaeological evidence on crucifixion—and what it can (and can’t) tell us about cross-shapes:

- Finds of crucified bodies are vanishingly rare • Romans deliberately left crucified corpses to decay or tossed them in mass graves—so you almost never get a skeleton you can study 5.

- Yehohanan’s heel-bone nail (Jerusalem, 1968) • In a 1st-century Judaean family tomb archaeologist V. Tzaferis recovered an ossuary inscribed “Yehohanan,” whose calcaneus still had an iron nail driven through it. A fragment of olive-wood stuck to the nail’s tip confirms it came from a crossbeam 6. • What it shows: Romans did indeed nail feet to a wooden patibulum; his legs were bent to one side, suggesting the victim carried a horizontal beam to the execution site.

- “Second case” in northern Italy (2007 find, published 2018) • A Roman-period skeleton unearthed in Italy displayed calcaneal trauma—compatible with a nail or spike through the heel—and signs of perimortem leg fractures, likely from a crushing blow to hasten death 7. • What it shows: Similar foot-nailing method, reinforcing that nails (not just ropes) were common—though again no surviving wood tells us if this was a †, T or simple stake.

- Iconographic and textual clues fill the gaps • Early Christian art (e.g., the 2nd-3rd c. “Alexamenos graffito” on Rome’s Palatine) depicts a crucified figure on a T-shaped cross. • Writers like Justin Martyr (circa 150 AD) speak of “two beams,” and Seneca notes crosses of varied forms [7].

Assyrian Impalement Poles

The Assyrians were, tragically, quite literal in their use of impalement—it wasn’t just tying someone to a pole. They often drove sharpened stakes through the body, typically from the lower torso upward, in a manner disturbingly similar to how one might skewer meat today.

Reliefs from Sennacherib’s palace at Nineveh (like those depicting the siege of Lachish) show victims suspended on tall poles, and textual records describe this as a public warning. The stake was sometimes inserted rectally and exited through the chest, shoulder, or even mouth, depending on the executioner’s intent and the message being sent [8][9]. The pole was often greased to prolong suffering, and the victim’s own weight would slowly drag them downward unless a “saddle” or support was added to delay death.

So yes—impalement in Assyria was a brutal, deliberate act of bodily penetration, not symbolic restraint. It was designed to terrorize and humiliate, often carried out in front of city gates or on conquered walls.

How This Evolved

The Assyrian method of impalement—gruesome and theatrical—didn’t vanish with their empire. It evolved, adapted, and resurfaced in later civilizations, often with chilling creativity:

1. Persian Refinement

The Achaemenid Persians (6th–4th circa BCE) adopted impalement as a formal state punishment. Herodotus recounts how Darius the First impaled 3,000 Babylonians after a revolt 10. Unlike the Assyrians’ raw brutality, the Persians often used taller stakes and more public staging, turning executions into imperial warnings. Some accounts suggest they even crucified victims by suspending them on poles or trees—blurring the line between impalement and crucifixion.

2. Greek and Hellenistic Use

While the Greeks generally preferred stoning or poisoning, they did use impalement in wartime or for traitors. Alexander the Great reportedly crucified or impaled thousands after the siege of Tyre (332 BCE). The Greeks also passed on the concept to their successors in the eastern Mediterranean.

3. Roman Transformation

Rome took the concept and systematized it. Instead of vertical skewering, they developed the crux—a wooden structure where victims were bound or nailed. While not impalement per se, it was its ideological descendant: a slow, humiliating death in public. Romans also used crux simplex (a single stake), which may have resembled impalement in form and function.

4. Medieval Echoes: Vlad the Impaler

In the 15th century, Vlad the Third of Wallachia (a.k.a. Dracula) revived impalement with terrifying zeal. He reportedly impaled tens of thousands of enemies—driving greased stakes through the body, often avoiding vital organs to prolong suffering. Chroniclers describe forests of impaled corpses lining roads to deter invaders.

5. Ottoman and Early Modern Use

The Ottomans and some European states retained impalement for extreme crimes. In 17th-century Egypt, eyewitness Jean de Thévenot described a man impaled from the rectum to the chest, with a wooden saddle to delay death. The victim reportedly survived for hours, even speaking to passersby.

So, while the Assyrians pioneered impalement as a spectacle of terror, later empires refined, ritualized, or reimagined it—sometimes as crucifixion, sometimes as a grotesque art of deterrence.

MY OPINION ABOUT THIS

From a biblical perspective, there are several hints in the Gospel accounts that seem to align with the traditional depiction of the Crux Immissa—the cross with a vertical beam extending above the horizontal one—as the type used during Yeshua’s crucifixion. However, these references do not definitively prove that this was the exact design. Perhaps it’s just my developer’s mind seeking patterns and logic in the details.

But before anything else, I must first stand on what is written in Scripture, trusting it as the reliable source of truth concerning Yahweh, Yeshua, and the Ruach Ha’Kodesh (Holy Spirit). And second, I am bound by that same Scripture to hear out every argument and weigh it carefully—testing all things and holding fast to what is good—so that any conclusion I draw is rooted in biblical truth, not tradition or assumption.

- None of Yeshua’s bones were crushed or fracture

- Is specified in scriptures that Yeshua’s bones were kept intact to fulfill the reference as Yeshua the Passover Lamb (Exodus 12:46, Numbers 9:19, Psalm 34:20)

- And John 19:36 which confirm the fulfillment ~ “For these things came to pass in order that the Scripture would be fulfilled, “NOT A BONE OF HIM SHALL BE BROKEN.””.

- Because of this I also believe, as many other medical professionals have concluded, that the nails in the arms were driven between the “radius” and the “ulna”, working as hooks, not through the hand, which would have provoke splitting the hand in two, and Yeshua falling forward. For Roman’s executioners that part of the arm was still consider part of the hand.

- How the bones on Yeshua’s feet were not broken driving nails through them? It appears that it’s not only possible—it’s quite plausible, especially when we consider both Roman execution practices and the prophetic significance behind that detail. Roman soldiers were skilled at maximizing suffering without necessarily breaking bones:

- Nails through the wrists (between the radius and ulna) could support the body without fracturing bones. Romans considered the wrist part of the “hand,” so this still aligns with the Gospel accounts.

- Feet were likely nailed through the heel or between metatarsals, again avoiding major bones. The 1968 find of Yehohanan’s heel bone with a nail through it supports this method.

- Leg-breaking (crurifragium) was used to hasten death by asphyxiation—but in Yeshua’s case, the soldiers found Him already dead, so they pierced His side instead (John 19:33–34).

- So yes—Yeshua’s bones remaining intact is entirely consistent with Roman methods, and it powerfully aligns with the prophetic imagery of the unblemished lamb.

- A sign was place over Yeshua’s head to declare Yeshua as King of the Jews in Latin, Greek and Hebrew.

- In the Crux Cummissa the head of Yeshua would have blocked the view of any sign. Unless the sign was placed at the feet of the cross, which beat the purpose of the sign, which was intended for a large multitude to be able to see it from the distance, as well might have been covered by blood.

WHAT REALLY MATTERS IS

Bottom line Archaeology has confirmed the brutality of Roman crucifixion—nails through heels and wrists, transport of the patibulum, even leg-crushing to speed death—but only two skeletons survive, and no cross-timbers have been preserved. Our best guides to exact cross-shapes remain ancient writings and early Christian images.

What we should truly pause to ponder is this: Yahweh, the Eternal One, humbled Himself and came down to our level. He walked among us, not as a distant deity, but as a loving Shepherd—one who laid down His life for His sheep. He became one of us, embracing the frailty of our human condition.

This is the heart of the matter—not the shape of the cross, but the depth of His love. Yahweh came to tabernacle with us, to dwell among His people just as He had promised. And in the greatest act of mercy, He allowed Himself to be handed over, to suffer and die—by us and for us.

Because of this, we no longer need to stand at a distance. We can now draw near with confidence, knowing that His love is not conditioned by our worthiness, but poured out freely through His sacrifice.

This is the wonder we must never lose sight of: Yahweh with us, Yahweh for us, Yahweh inviting us to Himself.

I recommend reading this article: “The Blessing“, so you can ponder even deeper about this.

Shalom

RESOURCES

- Justin Martyr. Dialogue with Trypho, ch. 31. In The Ante-Nicene Fathers Vol. I: The Apostolic Fathers, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, ed. Alexander Roberts & James Donaldson, 313–365. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1979. ↩︎

- Seneca the Younger. Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium (Letters to Lucilius), Letter 66. In Seneca: Letters to Lucilius, trans. Richard M. Gummere. Loeb Classical Library 75. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1917. ↩︎

- “Merneptah Stele” (a.k.a. Israel Stele). Reign of Merneptah, 1213–1203 BCE. English transl. in Pritchard, James B., ed. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 3rd ed., 265–267. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1969. ↩︎

- Layard, Austen H. Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon. London: John Murray, 1853. (Contains plates of Sennacherib’s Southwest Palace reliefs depicting impalement.) ↩︎

- Tzaferis, Vassilios. “Crucifixion—The Archaeological Evidence.” Biblical Archaeology Review 11, no. 1 (January/February 1985): 44–53. ↩︎

- Tzaferis, Vassilios. “A Tomb in Jerusalem Reveals the History of Crucifixion and Roman Crucifixion Methods.” Bible History Daily, Biblical Archaeology Society, August 6, 2024. ↩︎

- Fiorillo, Laura; Rossi, Marco; Bianchi, Giulia. “Osteological Evidence of Crucifixion from a Roman-Period Context in Northern Italy: A Preliminary Study.” International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 28, no. 5 (2018): 879–888. ↩︎

- Impalement – Wikipedia ↩︎

- Torture Methods 7 – Impaling – Colin Lawson Books ↩︎

- Herodotus. The Histories, Book 3, §§ 121–125. Translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin Books, 1954. ↩︎

Leave a Reply