What’s the proper name of the God of Israel?

The proper name of the God of Israel, as revealed in the Hebrew Bible, is YHWH (יהוה), often referred to as the Tetragrammaton—meaning “the four letters”.12 This name appears over 6,800 times in the Tanakh and is considered sacred. Because of its holiness, Jewish tradition avoids pronouncing it directly, instead substituting Adonai (“My Lord”) or Elohim (“God”) in spoken language. Some scholars reconstruct its pronunciation as Yahweh, though others historically rendered it as Jehovah, based on medieval Latin transliterations.3

When Moses asked for God’s name in Exodus 3:14, God responded with “Ehyeh-Asher-Ehyeh” (אהיה אשר אהיה), meaning “I Am That I Am” or “I Will Be What I Will Be”, emphasizing God’s eternal and self-existent nature.

What does the Tetragrammaton mean?

The Tetragrammaton refers to the four-letter Hebrew name of God: YHWH (יהוה). The term itself comes from Greek, meaning “four letters.” This name appears throughout the Hebrew Bible and is considered sacred in Jewish tradition.

The meaning of YHWH is often linked to the Hebrew verb “to be” or “to exist”, suggesting God’s eternal and self-sustaining nature.4 When God revealed His name to Moses in Exodus 3:14, He used the phrase “Ehyeh-Asher-Ehyeh” as we mentioned before it translate to “I Am That I Am” or “I Will Be What I Will Be”.5 This reinforces the idea that God is beyond time and existence itself.

Because of its holiness, Jewish tradition avoids pronouncing YHWH directly. Instead, substitutes like Adonai (“Lord”) or HaShem (“The Name”) are used in speech and prayer.

What’s the proper pronunciation, Yahweh or Yehovah?

Scholars overwhelmingly favor Yahweh as the best approximation of the original pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton over Yehovah (often rendered in English translations as “Jehovah”).

Here’s why:

- Linguistic Reconstruction:

Ancient Hebrew originally consisted only of consonants. The four consonants YHWH represent a name deeply connected to the Hebrew verb “hayah”—”to be” or “to exist.” This connection is highlighted in the biblical exchange in Exodus 3:14. Over time, because speaking this sacred name was avoided, Jewish tradition substituted the vowels from words like Adonai (“Lord”) when reading the text aloud. Modern scholars have revisited this practice and, through historical and linguistic research, concluded that the likely vocalization is Yahweh rather than Yehovah. This reconstruction is based on how the language evolved and on comparative evidence from early manuscripts and transcriptions .6 - Historical Developments:

The form Yehovah (or Jehovah) emerged in later Christian translations when the Masoretes—scholars responsible for preserving the vocalization of Hebrew scripture—inserted the traditional vowels from Adonai into YHWH. This process, while well-intentioned as a means to preserve the sacred name for liturgical reading, produced a hybrid form that does not reflect the original pronunciation. Modern linguistic studies indicate that the vowels chosen for Adonai were not likely the ones used in the divine name, making Yahweh the more historically accurate reconstruction7. - Consensus Among Scholars:

Even though the exact pronunciation can never be known with absolute certainty (since the ancient vowel sounds have been lost), a broad consensus in modern biblical scholarship supports Yahweh. This form more naturally aligns with the verbal root and shows up in comparisons with ancient transliterations and parallels in related Semitic languages.

How the Masoretic Text influenced these pronunciations or explore how these differences impact various translations and traditions?

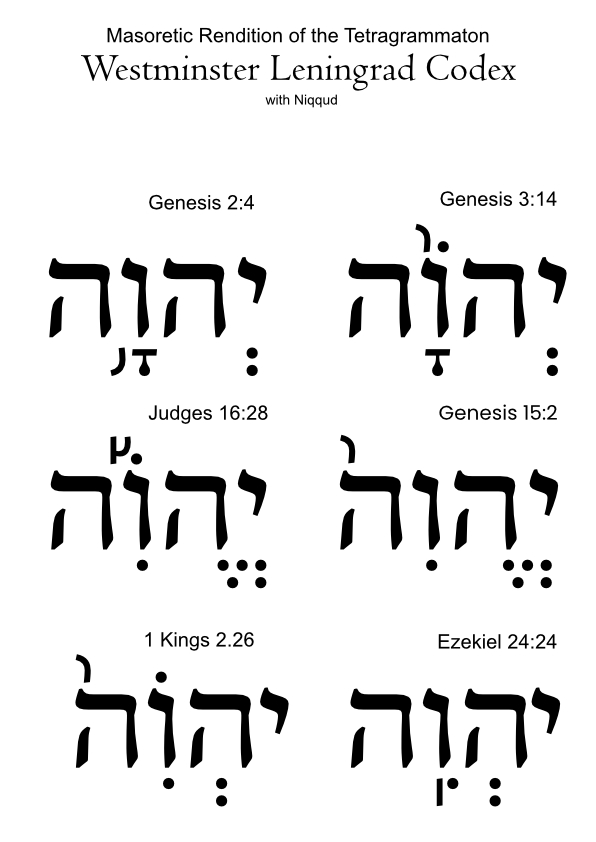

The Masoretic Text is key to understanding how the pronunciation of YHWH was passed down—and it also complicates our modern attempts to say the name properly. The Masoretes, Jewish scribes active between the 7th and 10th centuries CE, developed a system of vowel notation for the Hebrew Bible. For most words, these vowel points reflect the traditional sounds. However, when it came to the Tetragrammaton (YHWH), the name was held in such sacred esteem that it was never pronounced aloud. Instead, when reading, Jews would substitute the name with the word Adonai (“Lord”). To remind the reader of this substitution, the Masoretes deliberately inserted the vowel points of Adonai into the consonantal sequence YHWH—a process that, when combined, provides a vocalized form resembling “Yehovah” or “Jehovah” in many printed texts89.

This system, known as the Qere and Ketiv phenomenon, tells us that while the written text (the Ketiv) is YHWH, the traditional reading (the Qere) was Adonai. Because the vowels of Adonai were added to YHWH, the resulting vocalization does not necessarily reflect the original oral tradition of God’s name. Instead, modern linguists and biblical scholars compare the consonantal skeleton of YHWH with evidence from early translations, such as the Septuagint, and from comparative Semitic linguistics. This broader research suggests that the likely original pronunciation was “Yahweh” rather than “Yehovah” .

In essence, the insertion of the vowels from Adonai was a respectful precaution—a way to ensure the sacred name was not misused—rather than a prescriptive guide to its pronunciation. Today, while “Jehovah” has historical roots in those later vocalizations, “Yahweh” is favored in scholarly circles as it aligns better with linguistic reconstruction and ancient evidence regarding Hebrew pronunciation patterns.

The diverse vowelizations found in the Masoretic Text attest to how the name YHWH was carefully preserved to prevent it from being explicitly pronounced or audibly read aloud.

How do other manuscripts translate the four letters?

Here’s how different Bible translations and ancient languages handle the divine name YHWH:

📖 In Bible Translations:

| Translation | How it renders YHWH | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| KJV (King James Version) | LORD (all caps) | Follows Jewish tradition; uses “Jehovah” 4 times (e.g., Exodus 6:3) |

| NIV (New International Version) | LORD | Never uses “Jehovah” |

| NASB (New American Standard Bible) | LORD (footnotes sometimes say “Yahweh”) | Traditional rendering |

| ESV (English Standard Version) | LORD | Consistent with Jewish tradition |

| NWT (New World Translation – Jehovah’s Witnesses) | Jehovah | Uses “Jehovah” throughout Old Testament (~7,000 times); based on doctrinal preference |

| Jerusalem Bible | Yahweh | One of the few mainstream Bibles to use “Yahweh” throughout the Old Testament |

| Tanakh (Jewish Publication Society) | LORD | Jewish translations follow the tradition of not pronouncing the name |

🏺 In Ancient Texts and Languages:

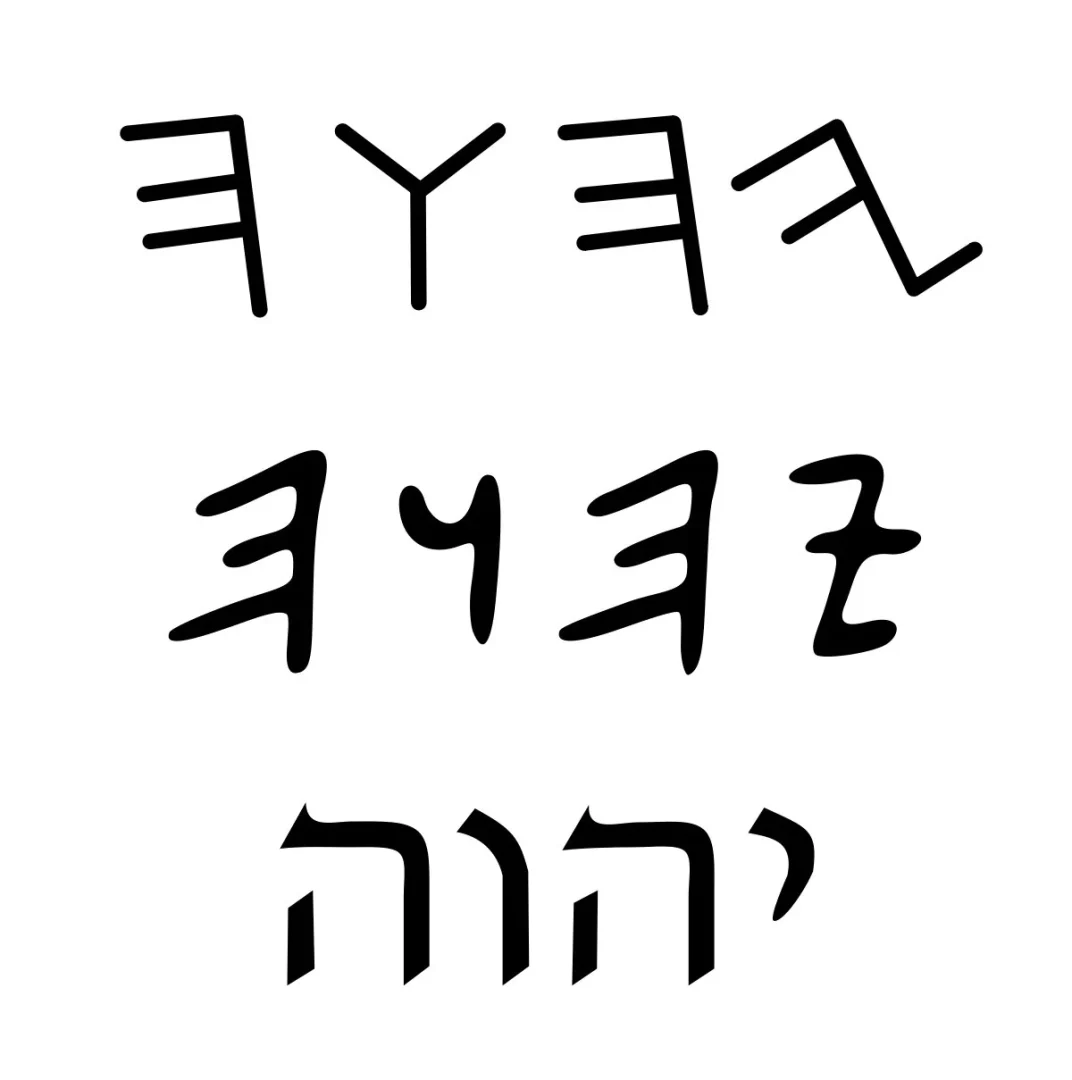

- Dead Sea Scrolls (Hebrew):

- Preserve the Tetragrammaton (YHWH) in paleo-Hebrew script (see above) even when the rest is written in Aramaic or square Hebrew.

- Sign of reverence—avoiding even writing it in the usual script.

- Septuagint (Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, ~3rd–2nd century BCE):

- Replaces YHWH with Κύριος (Kyrios), meaning “Lord”.

- In some older fragments, the Tetragrammaton appears in Hebrew characters within the Greek text.

- Samaritan Pentateuch:

- Uses a form close to Yabe, possibly an early variant or memory of the pronunciation.

- Philo and Josephus (1st-century Jewish writers):

- Refer to the name as ineffable (not to be spoken), but Josephus hints that it had four vowels, possibly supporting the Yahweh reconstruction.

Summary Table:

| Source | How YHWH is Rendered |

|---|---|

| Modern Jewish Use | Adonai / HaShem |

| Christian Tradition (historical) | Jehovah (later form) |

| Scholarly/Historical | Yahweh |

| Ancient Greek (Septuagint) | Kyrios (Lord) |

| Hebrew Bible | יהוה (YHWH) — no vowels |

What methods do scholars use to reconstruct YHWH’s pronunciation?

Scholars use a variety of interlocking methods to reconstruct the likely pronunciation of YHWH. These methods include:

- Masoretic Vocalization Analysis:

Although the Masoretes (medieval Jewish scribes) added vowel points to the Hebrew text, they deliberately inserted the vowels of Adonai (meaning “Lord”) into the consonantal sequence YHWH instead of preserving its original vowels. By comparing this system with other words whose vowels were preserved and by understanding the scribal traditions, scholars can isolate the vowels that likely did not belong to YHWH. This analysis helps disentangle the later liturgical vocalization from what scholars believe might have been its original pronunciation. - Comparative Semitic Linguistics:

Researchers compare YHWH’s consonantal skeleton with cognate words and deities’ names in related Semitic languages such as Ugaritic, Akkadian, and Arabic. Many languages in this family share similar root structures and vocalic patterns, so by examining these patterns, linguists can infer which vowels are most plausible. This comparative method leverages the known evolutionary rules that govern sound changes in Semitic languages, thus offering clues to the vowels that might have originally been used. - Analysis of Ancient Transliterations and Translations:

Early translations of Hebrew scriptures—like the Greek Septuagint—and the writings of early Christian and Jewish authors often provide indirect evidence. These sources sometimes offer transliterations or remarks regarding how the name was pronounced. When ancient translators rendered YHWH into their own alphabets and phonetic systems, they occasionally retained hints of the original vocalization. By studying these transliterations, scholars extract critical phonetic information that supports the “Yahweh” reconstruction over forms like “Yehovah.” - Internal Biblical Evidence:

Biblical passages, especially the famous self-revelation in Exodus 3:14 (“Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh” or “I Am Who I Am”), link YHWH to the Hebrew root “hayah” (היה), meaning “to be.” This connection indicates that the divine name is fundamentally related to existence and being. Evaluating the internal consistency of the language and its morphology helps narrow down the vocal elements likely associated with YHWH’s consonants. - Phonological Reconstruction and Sound-Change Rules:

Scholars reconstruct ancient sound systems by applying known rules of phonological evolution in Hebrew and early Semitic languages. By understanding how vowels and consonants shifted over time, researchers can simulate plausible ancient pronunciations. Combining this with data from inscriptions, such as those in the Paleo-Hebrew script, further refines the probable vocalization.

Each of these methods converges on the idea that the most historically and linguistically accurate rendering is likely “Yahweh.” By cross-referencing evidence from manuscripts, comparative linguistics, and ancient transliterations, scholars have built a strong case for this pronunciation despite the challenges posed by centuries of sacred tradition and altered vocalization patterns.

Is there an aspect of this reconstruction—perhaps the role of early Greek transliterations or the linguistic comparison with other Semitic languages—that you’d like to delve into further?

Please feel free to contact us via email at journey@returntosinai.org. If you have any questions, you can send them to questions@returntosinai.org. While I may not always have the immediate answer, I believe that questions inspire us to deepen our reflection. As a family, we will conduct research and get back to you with an answer, interpretation, or conclusion once we have explored the matter further.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while both forms are recognized—especially in historical Christian contexts where “Jehovah” became common—the evidence tips the scales in favor of Yahweh as the proper pronunciation of YHWH.

Resources

ARTICLE DIRECT LINKS REFERENCES

- https://hebrew4christians.com/Names_of_G-d/YHVH/yhvh.html ↩︎

- https://www.thebiblejourney.org/biblejourney2/48-the-jewish-world-of-the-old-testament/the-names-of-the-god-of-israel/ ↩︎

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Yahweh ↩︎

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tetragrammaton ↩︎

- https://www.christianity.com/wiki/christian-terms/what-is-the-tetragrammaton-meaning-and-usage.html ↩︎

- https://www.jesuswalk.com/names-god/yahweh_jehovah.htm ↩︎

- https://www.bereanpatriot.com/how-to-pronounce-gods-name-%D7%99%D7%94%D7%95%D7%94-yhwh-the-tetragrammaton/ ↩︎

- https://www.hebrewgospels.com/pronunciation-yhwh ↩︎

- https://www.2020scripturalvision.com/post/is-god-s-name-yahweh-or-jehovah ↩︎

Below is a comprehensive list of the major resources and references that have informed our entire conversation about the Tetragrammaton, the reconstruction of YHWH’s pronunciation, and related ancient scripts and linguistic methods. These sources span scholarly books, online articles, biblical texts, and discussion forums that provide background on the theory and evidence behind our current understanding:

Biblical Passages

- Exodus 3:14

- Key Passage: “Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh” (“I Am That I Am” or “I Will Be What I Will Be”)

- Role: Central to understanding the association between YHWH and the Hebrew root “to be.”

- Deuteronomy 6:4 (The Shema)

- Key Passage: “Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God, the LORD is one.”

- Role: Illustrates the monotheistic declaration foundational to Jewish faith and implicitly related to discussions of the divine name.

Academic Books and Monographs

- Scripts and Writing Systems

- The World’s Writing Systems – Edited by Peter T. Daniels and William Bright

- A comprehensive reference covering the evolution of scripts (including Proto-Sinaitic, Proto-Canaanite, Phoenician, and Hebrew).

- Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet – J.T. Hooker

- Offers detailed insights into early alphabetic systems and the transition from pictographic to phonetic scripts.

- The World’s Writing Systems – Edited by Peter T. Daniels and William Bright

- Languages and Etymology

- The Semitic Languages – Robert Hetzron

- Explores the structure and evolution of Semitic languages, including the root relationships that inform the pronunciation of divine names.

- A History of the Hebrew Language – Angel Sáenz-Badillos

- Provides an in-depth look at how Hebrew evolved from its ancient origins to its modern form.

- The Semitic Languages – Robert Hetzron

- Historical and Biblical Context

- Who Wrote the Bible? – Richard Elliott Friedman

- Discusses the composition and authorship of the Torah and related biblical texts.

- The Bible Unearthed – Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman

- Combines archaeology and history to examine early Israelite culture and scripture development.

- Who Wrote the Bible? – Richard Elliott Friedman

Online Articles and Resources

- Ancient Scripts and Linguistic Reconstruction

- Ancient Scripts: Semitic

- An online resource that provides concise overviews of early Semitic scripts, including Proto-Sinaitic and Proto-Canaanite.

- Omniglot’s Phoenician & Hebrew Scripts

- Offers visual charts and comparisons of various ancient alphabets, detailing evolutions from Phoenician to modern Hebrew.

- Ancient Scripts: Semitic

- Etymology and the Divine Name

- Jewish Virtual Library – “The Origin of the Hebrew Language”

- Discusses the etymological background of terms like “Hebrew” and contextualizes the significance of names.

- My Jewish Learning – “Ivri and Hebrew: What’s in a Name?”

- Explores the linguistic and cultural roots of the term “Hebrew,” touching upon early usage and Biblical implications.

- Jewish Virtual Library – “The Origin of the Hebrew Language”

- Masoretic Text and Biblical Scholarship

- Jewish Encyclopedia – Entry on the Masoretic Text

- Provides historical context and details regarding the development of vowel pointing in the Hebrew Bible.

- Biblical Archaeology Society – Articles such as “Torah and Egyptian Hieroglyphs?”

- Examines how ancient writing systems compare with the scriptural texts and the evolution of biblical writing practices.

- Jewish Encyclopedia – Entry on the Masoretic Text

- Evolution of the Alphabet

- Stanford University Resources on the Evolution of the Alphabet

- Visual and scholarly resources that compare ancient scripts (Phoenician, Paleo-Hebrew) with developments leading to the modern alphabet.

- Stanford University Resources on the Evolution of the Alphabet

Scholarly Methods and Comparative Linguistics

- Methodological Approaches to Reconstructing YHWH’s Pronunciation

- Masoretic Vocalization Analysis:

- Study of how medieval Jewish scribes (the Masoretes) notated texts and deliberately used the vowels of Adonai to mark the sacred Tetragrammaton.

- Comparative Semitic Linguistics:

- Research comparing the consonantal skeleton of YHWH with cognate terms in related languages (Akkadian, Ugaritic, Arabic).

- Examination of Early Transliterations:

- Analysis of how ancient translations like the Septuagint rendered the divine name, offering indirect clues through Greek phonetics.

- Phonological Reconstruction:

- Application of known sound-change rules in Semitic languages to simulate plausible ancient pronunciations.

- Internal Biblical Evidence:

- Correlating the usage of YHWH with related biblical passages (e.g., Exodus 3:14) to understand semantic and morphological implications.

- Masoretic Vocalization Analysis:

Online Discussion Forums (Supplementary Perspectives)

- Reddit Threads and Academic Q&A

These discussion threads, while not primary scholarly sources, provide insight into current debates and diverse viewpoints: - r/AcademicBiblical: Threads exploring why the original pronunciation of YHWH is challenging to reconstruct.

- r/AskHistorians: Conversations on the evidence supporting the pronunciation “Yahweh” and the historical context of its usage.

- r/linguistics: Discussions regarding the evolution of the divine name and the methodologies underpinning current reconstructions.

This curated list provides a cross-section of the resources that have shaped our conversation—from ancient texts and modern scholarship to online discussions that reflect the ongoing dialogue in the academic community. Each resource contributes to understanding both the historical context and the linguistic challenges in reconstructing the original pronunciation of YHWH.